The Scent of Dried Roses Read online

Page 30

James does not obviously change, but he is given to fits of irrational rage about nothing in particular. I try to tell him that it is OK for him to be angry at Jean for leaving him and he seems relieved. But like my father, he has a personality that is rooted and sure. He is good at denial, or, if you prefer, he has a certain focus; his workmates at the hairdresser’s nickname him, affectionately, ‘The Ostrich’ for his ability to filter out unwelcome information.

Nevertheless, like Jack, James feels guilty. He thinks of the educated, well-heeled girlfriends that he would not bring back to the house out of shame at its ordinariness and fears that Jean might have thought he was ashamed of her. He thinks of the times he mocked Southall in front of Jean. These things he lives with, and his life does not collapse. Instead of our family flying apart, it becomes closer than ever. We are, and remain, friends. There are no recriminations between us.

James makes a success of his life, building up his own business as a hairdresser in his own shop in Soho. He watches football, he takes Ecstasy, he drinks lager, goes clubbing and sleeps with lots of pretty girls. He misses Jean, but eventually she fades. All of us fade, all of us must. James is happy.

Of Jeff it is harder to speak, because after the funeral he returns to New Orleans. The resentment between us at first does not appear to have gone away. I write an elegy for Jean to be read at the funeral and show it to my father. He is moved to tears and grateful. I then show it to Jeff for his approval and I am stunned when he angrily rejects it. I am immensely hurt and do not understand that the reason he is angry is that I am even now claiming ownership of what is also rightfully his. That it is not what I have written, but the fact that it is me who is writing it, that it is me who is claiming ownership of the meaning of Jean’s death. We have a screaming row, almost physical, as my father pulls us apart as he once did in our childhood. The funeral cortège pulls up outside. We are duly ashamed. Life, it seems at such times, is only playing at grown-ups after all.

By the time we reach the crematorium we are reconciled. There are more than a hundred people at the funeral, including my Uncle Alan, who puts his head on Norman’s shoulder and cries for the first time in his life that anyone has seen. The elegy is read. After it is all over, Jeff, with great dignity, apologizes and we embrace. I did not then understand that I also owed him an apology.

It appears that – perhaps and at last – my mother’s death does unblock something in our relationship. When we meet in the years after, on occasional visits to each other’s countries, the old rivalries seem to have faded. Maybe we no longer have anything to prove to each other, or perhaps the person who we really have to prove it to is not around, even in our imaginations, to judge any more. Jeff does not seem to feel any guilt about Jean’s death and this sometimes irritates me, that he so easily assumes that there is no fault on his part, that he could even have had the slightest portion of responsibility. Yet I come to truly like him, and I hope he comes to like me.

We are still very different people. He thinks I am pretentious, I think he over-simplifies, and we remember very different lives. He claims that he never had any resentment towards me in the slightest and that his childhood was absolutely happy. As I say, each of us has his story. But now we tolerate each other, and get on with the business of being brothers. For the first time, somehow, this closeness has become possible, even to the extent that at one point Jeff tries to move back to London, lock, stock and barrel, after twenty years abroad. In the end, and at the last moment, he cannot find the money or the will. He stays in New Orleans with his wife and the two children Jean will now never see. He, too, is happy.

For me, Jean’s death once again proved something that I have difficulty in accepting: that life is deeply unpredictable and random, and immune to most attempts at control. Of course Jean’s suicide itself is ample proof of that, for nothing could have been as truly unexpected as that strange act, however much hindsight seeks to make sense of it, but it does not stop there. I expected, through all my life, that the death of one or other of my parents would crush me, so close did I always imagine us to be. For it to happen in such a way, and at a time when I had recently been acutely depressed, I could only anticipate that I would fall, very quickly, to pieces. In fact, nothing of the sort happens. I grieve, I weep, but all the time I simply continue to feel stronger and stronger. Having suffered years of depression – which is a blocking of emotion – even the feeling of pain and loss is welcome in that it affirms that I am, finally, human.

There is no solution to unhappiness of course. My mother’s death makes me very unhappy indeed, as is natural and proper. But it does not make me depressed, for it moves through and beyond me, changes me and then leaves, to recur in ever less frequent – though never shallow – waves. It is real grief, with a beginning and a kind of end, with a source and a resolution. It is the opposite of depression, which is a desperate attempt to avoid change.

And now I am changing. Whether it is as a result of my mother’s death or my own breakdown, I do not know. I have lost the childish conviction that the world is subject to my desires, and I know I must give it its due. In other words, I begin to understand what my father has always understood: that life has a shape that we must know through a sort of secular faith and must then try to trace.

And so I wait, hopefully, instead of smashing myself – as I once did – against sheer cliffs of circumstance. I try to have a little bit of faith. I risk a little bit of hope, even. And sure enough, six months after my mother’s death, I am selected from several thousand applicants for a job as a researcher with a television company. Within two months of taking it on, I am made a producer and am running my own morning arts news programme for Channel Four.

Television, though, is not for me. My experiences have pulled me apart from my old, thrusting self and I cannot help but find the whole thing ludicrous, with its power plays and secret politics. I resign and become a journalist, this time for quality newspapers. Still this is not enough and my ache to become a writer, always latent, pushes me out of journalism and into my room, where I start to write a novel.

My depression has not entirely gone away and I remain subject to days when everything seems hopeless and sad, and when I hate my life and am filled with regret. I have stopped taking the antidepressants, but on one occasion, having read a story about Prozac in the newspapers, get the doctor to write me a prescription when I am feeling particularly down. It works; the depression dissipates like a cloud. Yet I still remain unconvinced that it is all in my body. There is something in the way I choose to see things.

I fall in love again and marry a woman from a background similar to mine, an escapee from an ordinary, suburban background. She is a polytechnic lecturer, quiet, attractive, Italian. Neither of us wants children, yet she falls pregnant twice, by accident or carelessness or unacknowledged choice, and we find ourselves with two daughters. This most ordinary of developments, stumbled into accidentally, like most things in my life, which I would have once disdained as dreary, turns out to be the best thing that has ever happened. Now I hardly get depressed at all; in fact, I feel almost daily, plain joy, routine exuberance.

However, my writing career is not going well and my novel is universally rejected. I become despondent and pessimistic once more, for if I am not a writer, then I have no function beyond being a father and that does not feel like enough. This, Prozac cannot cure. I cast about for a subject, yet I cannot think what story I could write, for my life is so ordinary and unglamorous and stupid. And then it occurs to me what my mother’s final, and greatest, gift to me truly was.

And so this has been the story of ‘what happened’ and how our lives unfolded. But it does not answer Jack’s question, Why, Jeannie, why? It does not tell you why I went mad, or if I am guilty, or if my book is not really an autobiography and a biography, but in fact a confession, an attempt at expiation. For consider the blow I dealt her, unloading, wilfully, my own sadness on to her. Think of her final plea, unheard by m

e, I don’t think I can last that long. Judge me, if you wish. But let me first finish my story.

To begin to answer the question ‘whose fault?’ – and you can only begin to answer anything – you have to understand depression. You have to understand that particular variety of despair.

The image that haunts me most of Jean’s last days is that of her hurtling down Somerset Hill in her old blue Jetta, crashing insanely from kerb to kerb. What is going through her mind, in this one and only moment that her almost supernatural self-control deserts her and all the chaos and fear that are lurching under her tidiness and perfect poise swing into public view? If only she had crashed, then –

If only, one of the great clichés of the suicide survivor, or the survivor of almost any disaster, along with Why? and Why me? If only I had done x, if only y had done z. Yet life is sometimes random and frequently unfair, as my father has always instinctively known, however much we wish to apportion order and, therefore, blame. Presuppose a just universe – and how many of us wish it, for it gives us the hope of controlling our destinies – then if something goes wrong, it follows that you must have done something wrong to deserve it. Then you have to find out what it is and do penance. Wasn’t this the trap that both of us fell into, when we became suicidal? We had beliefs – in my case secret, hidden even from myself – in a kind of immutable order that held us accountable. But let go of that childish belief, accept randomness and uncertainty, tolerate chaos, and the whole thing slides into place. That place is shapeless, that place is always moving and out of focus, but it is the reality of things.

To put it briefly, I cannot ever know if I am guilty, but if I am, I no longer have difficulty forgiving myself. I have decided that I would rather not be such a supernaturally good person – as my mother fantasized herself, finally, to be – that it involves me killing myself, or living a life of despair, in order to prove it.

I know now, without any doubt at all, that depression is an illness and that my mother and I both suffered it. But I also know that the explanation does not stop there, that depression is a very particular type of illness, in that it seems to hinge on your interpretation of the world, the story you tell yourself.

How can this be true of an illness? Ask yourself why is it that my Uncle Arthur dies of a heart attack in 1981? The conditions are quite simple, uncontroversial, you might say. He has a weakness in his heart, as a result of a childhood illness, in this case rheumatic fever. His personality tends towards the over-conscientious, hence he worries and frets about doing well enough at his job as manager at Dolcis. In his own way, like Jean and I, he is a perfectionist, never quite satisfied with himself. This anxiety and susceptibility to stress – his doctor tells him quite clearly, after he suffers his first heart attack in 1979 – may one day be translated into the physical realm and kill him. He advises Arthur to take retirement.

Arthur, however, is driven by his generation’s bred sense of loyalty to the employer and his own high standards. He carries on working, and working hard. He cannot stop worrying about what he considers to be his responsibilities. One day, at a highly charged executive meeting, he slumps forward on the table, dead. Nobody questions the fact that a combination of childhood damage and psychological stress has led to a catastrophic illness. It seems like common sense.

However, while heart disease is without stigma, unladen with values, mental disease is contorted under the weight of both. So the idea that I may suffer from a physical, possibly inherited vulnerability in the chemistry of my brain, combining with a certain psychological disposition which, under stress, leads to a ‘brain attack’, is… sticky, in the way a coronary is not. The brain is the part of the body that thinks, and thinking is the activity that most completely expresses identity, defines me as a personality. The idea that mood, values, belief, thought itself can simply be the coral outcrop of a physical organ is disturbing for most people.

If what Jean and I went through is indeed an illness, then it is one that in some ways is worse than any other. For the terrible thing about depression is that you don’t quite believe that anything is malfunctioning. And unlike, say, schizophrenia, it may be that no one else will notice either. It is not like cancer or AIDS, when you can be brave, or cowardly, but at least you will have a condition with which you can have a relationship, a coming to terms. Depression is the only potentially fatal illness that, right up until death, you may not know you have.

Even if you recover, you cannot say for sure that you have been physically ill; there are plenty of people, both professional and lay, who will insist that you were not, that it is all down to you. And if you are a depressive, a part of you will be only too ready to agree, since that is what depression is about – not, as some would have it, a shrugging off of responsibility but the reverse: a sort of addiction to responsibility, or, to be precise, blame. If, on the other hand, you are ‘lucky’ and are recognized as being – how I still hate the phrase – mentally ill, you are as liable to face fear and pity as the sympathy and understanding that a less threatening illness might elicit.

This paradox between mind and body – between illness and attitude – is not as insoluble as I once thought. If it is easy to believe that my Uncle Arthur’s heart attack was partly the result of a certain kind of relationship to the world, if you believe that some cancers stem from a kind of impacted anger – and both views are backed by good medical evidence – then it is no great trick to think that a physical depression can be caused by culture, by a way of seeing and imagining the world, and yet end up as a physical illness.

Of course, there are many kinds of depression, just as there are many kinds of pain. Some are largely physical, some mainly psychological. It’s also worth remembering that not all suicides, by any means, are depressives. But where depression exists, it always has what you might call an existential ingredient. The provoking question is, if anxiety can lead to coronary thrombosis and anger can lead to cancer, what kind of thinking leads to depression?

Depression is about anger, it is about anxiety, it is about character and heredity. But it is also about something that is in its way quite unique. It is the illness of identity, it is the illness of those who do not know where they fit, who lose faith in the myths they have so painstakingly created for themselves. Thus, in this current confused, self-hating England, it is spreading like a virulent, dimly understood virus. And it is a plague – especially if you add in all its various forms of expression, like alcoholism, anorexia, bulimia, drug addiction, compulsive behaviour of one kind or another. They’re all the same thing: attempts to avoid disappearance, or nothingness, or chaos.

Once I realize this, the reason for undertaking this book, which, I can now admit, has sometimes seemed obscure while writing, begins to become clear to me. For in finding a solution to identity, you begin to find a solution to depression.

Depression is not grief. It is an attempted defence against the terror of losing your invented sense of self: who you believe yourself to be and the way in which you think the world operates. It is fear of annihilation, of doubt, of insignificance. It is a reaction to a very particular kind of stress, the kind that brings into question the world that you, being human, have to imagine and reimagine, maintain and defend every moment of every day, in order to keep chaos at bay. When that stress is acute enough, depression follows on, sometimes so deeply that it is not only refracted in the brain – like all mental activity – but sticks there, a bad habit, or a fishbone lodged in the throat.

When my mother decided to kill herself, she was both crazy and entirely sane, both severely ill and well. She hanged herself because her story, her idea of herself as a successful wife and mother – the only real test of worth that she knew – was no longer sustainable in her shocked mind. She had no function, now that James had left home. She had not succeeded in protecting me from whatever it was that left me wanting my own death – that was left to medicine. Her oldest son had divorced, then remarried without extending her an invitatio

n to the ceremony. The story of her life no longer stood up, but she was not prepared to let it collapse. She was more frightened of that than of the noose.

Larger forces were at play. As Southall rotted, another scrap of identity went, the idea, so large for her generation, of pride in being English. At the same time, the illness that is depression cut her off from her own feelings, separated her from Jack.

Under the terrible magnifying glass that depression, once set in train, becomes, all these things expanded into catastrophes that were her fault, since in her view of the world they had to be somebody’s fault. It wasn’t in her philosophy to blame accident or anyone else. Thus it was that she no longer deserved to live. She knew that to carry on living meant the person she had always imagined herself to be could no longer be sustained. She believed, having lost that person, she would became instead a burden, a nuisance, and without pride. She killed herself to save herself, to avoid change, to duck meaninglessness. And, since depression feels like a collapse of faith, she could see no hope of things getting better.

As for me, I wanted to die for much the same reason as my mother: because it was the only way my interior life would go on making sense; because killing myself was the only way I could preserve my identity – that is to say, my story. Oh, we want to pin things down so much, get them just so. We are so afraid of the alternative. We do not believe that the water will buoy us up, so we thrash around, and drown.

Like Jean, like all of us, I was a prisoner of my own logic. Having at one point in my life refused, or been unable, to mourn a particular loss, I had come to feel emotionally dead and in mental torment, and there could be only one story that would explain that to me (and a story had to be told, you can’t stop yourself). I believed, like many good liberals, indifferent Christians and prime-time Americans, that our inner selves were the sum total of all our choices. Since I was in a kind of mental hell, it had to follow that I was wicked and damned. Nothing else made sense, and to make sense of things is a need, it seems, greater than life itself. If you want to get historical about it, you can talk about nationalism, Nazism, holocausts, ethnic cleansing; they are all merely ways of holding fast to your story, of avoiding the awesome responsibility that accepting uncertainty and insignificance entails.

When We Were Rich

When We Were Rich The Seymour Tapes

The Seymour Tapes The Love Secrets of Don Juan

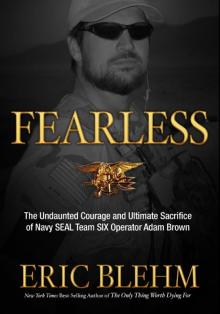

The Love Secrets of Don Juan Fearless

Fearless How To Be Invisible

How To Be Invisible Seymour Tapes

Seymour Tapes The Scent of Dried Roses

The Scent of Dried Roses The Last Summer of the Water Strider

The Last Summer of the Water Strider Rumours of a Hurricane

Rumours of a Hurricane Love Secrets of Don Juan

Love Secrets of Don Juan