How To Be Invisible Read online

Page 4

Having briefly examined my cadre of new friends – Lloyd Turnbull, Susan Brown, and two boys both called Wayne, Wayne Fleet and Wayne Collingham – I decided to start my homework. But I found it very difficult to concentrate.

I tried to make a list of some Christmas presents I might like so I could give Melchior and Peaches plenty of time to shop around. I was hoping for a telescope or an iPod, and possibly a decent bike and the second volume of the George R. R. Martin series. Then I ran out of ideas.

I don’t know why I had been putting it off, but it was then that I picked up the How To Be Invisible book again. Of course I hadn’t forgotten about it. But somehow it had unnerved me, because what I had seen the previous evening was impossible, and impossible things are frightening.

I still could not figure out why the book was behaving in such a strange way (if books can be said to “behave”). What I had seen – words on a page only appearing when reflected in a mirror – made no sense. Perhaps the stress of the move to Hedgecombe was giving me hallucinations.

I decided I would check one more time, to make sure I hadn’t completely lost my faculties, and then – if I had indeed observed the book accurately – show it to Melchior so that he could assess the book’s unusual properties. It might prove to be one of the most exciting discoveries of all time, and Melchior would become famous and we would have plenty of money and then all our troubles would be over.

I picked the book up and flicked through it. The pages were still blank. It was scientifically impossible that they would not still be blank when I held them up to a mirror, of course. I started to consider the possibility that I was not merely imagining things – that I was, in fact, mentally ill.

Children who attend special schools, like I had, register unusually high rates of psychological disorder. I had a genius uncle who believed that starlings were flying spiders. He threw himself out of a second-floor window after watching Peter Pan, thinking that if he really believed it enough, he would be able to fly. He broke his leg.

That’s what happens when you think unscientifically.

I very cautiously held the pages up to the mirror again. I was almost relieved to see that there was still nothing there. At least, there was nothing at all on the first page after the title page, whereas before there had been all that stuff about the “shadow of nonage” – whatever “nonage” was – and “That which matters is not of matter made”. Clearly I had been letting things get to me, but now it seemed I had recovered my wits. The page remained resolutely blank no matter how many different angles I held it up at in front of the glass. Apparently I wasn’t mentally unstable after all.

I was about to throw the book away – properly away, in the outside bin so that when the rubbish truck came the next day it would be got rid of once and for all – when, on impulse, I decided to turn the page. And there they were again – words, reflected in the mirror, the right way around.

I felt a giddy sensation in my stomach, but also a tangible rush of excitement. Something impossible was happening – again. But then, the way I figured it, impossible things were perfectly possible. Because although science always thinks it’s so matter of fact, it’s anything but. Incomprehensible things happen routinely. Thinking, for instance, about the Mystery of the Magic Atom Experiment made me think that the invisibility book might not be so impossible after all.

Whether the book was impossible or not, the words that I could see in the mirror were definitely there – although once again they were flickering and faint.

I copied them out on a scrap of paper in case they disappeared. This is what they said:

Everything is space, within and without.

The mirror is a wall that reflects all your doubt.

Run through that wall without any fear

For all that is solid will soon disappear.

Hold these words pressed hard to your heart.

The seen and unseen must surely part.

I didn’t understand. I hated poems anyway – they never made any sense, and this one was no exception. My mother was always trying to get me to read poems and “proper books” instead of what she calls “trashy science fiction”. But although you can lead a horse to water, you cannot make it bloody well drink.

Just as I was staring at the words, trying to figure out what they meant, there was a knock on the door. It was probably Melchior. Peaches never knocked, she just barged right in without a word.

But when I opened the door, it was Peaches after all. Unusually for her, she wasn’t wearing any make-up. Her face looked tense and strained. I thought that she’d been crying. She tried to smile as if she was happy, but that’s just one of the ways in which grown-ups lie.

Without speaking, she went over to the chair next to my bed. She moved the big jumble of books off it and put them on the floor, which was covered with the previous day’s – and the day before’s – dirty clothes. Normally she would spend between thirty seconds and one minute going on about this and telling me that she was sick and tired of having to clear up after me, et cetera, but this time she made no comment.

Somehow I already had a suspicion of what she was going to say. As I expected, she lied about it.

“Dahlin’, I’ve got something very important to tell you.”

I said nothing.

“I suppose you’ve noticed that your father and I haven’t been getting on all that well lately. All has not been sweetness and light.”

I suddenly had a clenched-fist feeling in my stomach.

“I don’t know how to say this, so I’m just going to come right out and say it. Your father has decided he needs a bit of a break.”

“What kind of a break?” I said, haltingly. “Like a holiday?”

I was playing dumb, but I knew what she meant.

“Not like a holiday, no. More like – well, a space in which he can think and find a little air.”

“Isn’t there enough air here?”

“Don’t be obtuse, dahlin’. This isn’t easy for me.”

“Where is Dad?”

“He’s just gone out for a while. He’ll be back soon. I think he’s a bit upset.”

“So what are you saying?”

“Well, he – we – were just thinking about him moving somewhere nearby for a little while, just until he sorts himself out.”

There was a long silence.

“How do you feel about that, dahlin’? I know it must come as a shock, but it might be better for all of us – at least in the short term. I’m sorry. I’m sure everything is going to be alright in the end, but we have to be practical, don’t you agree?”

“Will he be here for Christmas?”

“Of course he will.”

“I still don’t understand. Why does he need more air?”

She tried to give me a hug, but I kept my hands very firmly by my sides. I realized that my hands were clenched into little fists. I looked at them. The knuckles were all white.

I wanted to ask her what I had done to make Melchior want a bit of a break from me, but I knew she would just pretend that it had nothing to do with me. I wanted to ask her how the hell I was meant to feel about it, other than furious, sad and confused. But I found it hard to say those kinds of things straight out.

Instead I just said this: “Are you going to divorce?”

She pretended to look surprised, but I knew she couldn’t have been, because I’d heard her use the word “divorce” only the day before, so they must have talked about it. And now if Melchior was moving out, then they must actually be doing something about it, only of course they wouldn’t be straight with me because it might upset me.

It would have been hilarious if it hadn’t been so bloody sad.

“Of course we’re not going to get divorced. For a start, we’re not even married.”

This infuriated me. Did she think I was a bloody idiot?

“You know what I mean,” I said.

“I’m sure it won’t come to that. You know that you

r father and I love you very much.”

I could hardly hear what she was saying because I felt like my head was about to explode with the blood pumping through it, and I thought my fingernails were going to cut into my hands, I was clenching them so tightly.

Just then, the phone downstairs began to ring, and Mum got this expression on her face that made her look very relieved, and she said that she had to go downstairs and answer it. It was as if she could hardly wait to get out of the room.

“I’m sorry, dahlin’. I’ve got to take that. I think it’s about my book. I really do think it’s going to be published. Isn’t that wonderful?”

“Yes.”

“I’m sure everything is going to be OK. When your father gets back, he’ll talk to you about everything. I know it must be very confusing for you.”

Then she went to answer the phone, a little too quickly, leaving me to my own devices.

I imagine that when adults hurt their children it is as if they are hurting themselves and they want to get it over as quickly as possible.

I did not expect her to come back any time soon. I had no doubt that the urgent phone call was going to take plenty of time. As for Melchior, where was he? It would have been nice if they could have sat down with me together and told me what was going on. It made me feel very angry.

On the other hand, I was rather glad he hadn’t been there in a way – my father is even worse than my mother at talking about things that are “difficult”, though I didn’t know what was so difficult about telling the truth.

I sat down on the chair where Peaches had been sitting. It was still warm from her body. I started to have strange thoughts. It was weird to think that I had actually come out of that body. Biology is even stranger than physics sometimes. For example, people talk about how life began on the Earth by saying stuff like, “Well there was a one-celled creature and it evolved into all of us.” But where did the one-celled creature come from? Did it evolve out of rocks?

Then my weird thoughts dried up, and my head emptied. I stood up and sat down, then I stood up and sat down again. I didn’t know where to put myself. It was as if I was trying to get out of my body and go somewhere else, but of course I was unable to do so.

I became aware that I was grinding my teeth, something I normally do only in my sleep. My head was hot. I could feel the blood pumping in my ears. I looked at my hands. They were trembling slightly.

Looking back, I don’t think I had ever felt so angry in my life. I was angry with stupid bloody adults who thought only of themselves. I was angry with stupid bloody Peaches for running out of the room, and I was angry with stupid bloody Melchior for not sitting down with me and talking to me like a grown-up.

Above all, I was angry at stupid bloody me for being so stupid that I couldn’t do anything to stop them splitting up, and for not being able to work out why I had made it happen in the first place. Was I really so bad?

I got up again, and noticed the book and the words I had written down on the scrap of paper beside it. I stared at them. Suddenly it was obvious what they meant.

Everything is space, within and without.

The mirror is a wall that reflects all your doubt.

Run through that wall without any fear

For all that is solid will soon disappear.

Hold these words pressed hard to your heart.

The seen and unseen must surely part.

I understood now. The book wanted me to jump into the mirror.

It wanted me to hold the book and run through the mirror – without any fear.

That last part was easy. I was too angry to feel afraid. I thought that if I gave the mirror a good smashing, it might make me feel a lot better about myself, and it would also get rid of the stupid picture of me that it showed every time I looked into it – all small and scared and silly-looking, with black skin and nubby hair and a skinny, spotty body.

I grabbed the book and held it against my chest – hard to my heart. I was ten paces away from the mirror, and I didn’t even think. I ran as fast as I could, head first, right into it, and waited for the sound of breaking glass to fill the air. That would show my mother there were more important things to do than take a stupid phone call when your son’s head was about to explode.

But no sound of breaking glass came. Instead, there was silence, deep and dark.

CHAPTER FIVE

HOW TO BE INVISIBLE

Before I relate what happened next, I will continue explaining the Mystery of the Magic Atom Experiment. It will make it easier to believe what happened to me when you understand the improbable things that occur in nature.

I had reached the part of the explanation where the atom gun – or cannon, or Kalashnikov, or Thompson sub-machine gun – was firing atoms at a wall in front of which was a screen with two slits in it.

I know what I would expect to happen. If you fired a machine gun at a wall, in front of which was a bullet-proof screen with two slits in it, you would – obviously – expect to see two slit-shaped rows of bullet holes in the wall behind the screen instead of one.

That’s exactly what you would get if you fired a normal gun at the wall and the slits were big enough to let bullets through.

But when you fire an atom gun at the screen with slits in, something completely different happens.

There are no lines of atom holes in the wall. There are no slit-shaped patterns.

What you see is a single swirly pattern of atom traces spread all over the place, in fanning-out, overlapping, wave-like shapes.

It is as though you have not been firing atoms at the slit, but water bombs which have exploded on impact.

Imagine – the moment the atoms went through the slits, instead of going BAMABAMABAMA and slamming into the wall like bullets, they went SPLODGE SPLODGE SPLODGE, and suddenly turned into something like water which spread out like waves.

Which is extremely weird. How can atoms fired through one slit behave like bullets and atoms fired through two slits behave like water bombs? Surely it has to be one or the other?

Or maybe not, you say. Maybe it’s no big deal. After all, despite the fact that they are just small chunks of stuff, atoms are bizarre things. Maybe when the atoms go through two slits they bang into one another on the other side of the screen and explode or something, leaving a great splodgy mess on the wall instead of two nice neat little slit patterns – rather like bullets might smash into one another and explode into smithereens.

The scientists performing the experiment thought this might be the case too. Then they thought the atoms might be going SPLODGE SPLODGE SPLODGE because they were interfering with one another. So they repeated the experiment – but this time firing only one atom at a time.

They fired a single atom and waited until it had either bounced off the screen or gone through a slit and hit the wall. Then they fired another one, then another.

And so on, until – you might expect – they eventually got a double pattern of slit-shaped atom holes on the wall.

But that’s not what happened.

When there was one slit there was a single long, slim pattern on the wall, as if little bullets had gone through the slit and hit the wall behind.

But when there were two slits, once again – SPLODGE SPLODGE SPLODGE. There were atom traces all over the place, making a pattern like waves on the wall.

The atoms weren’t interfering with one another. They were behaving differently according to how many slits there were in the screen.

Which begged the earthshaking question: How did the atoms in the atom gun know that there was a second slit so that they could decide to behave like water bombs instead of bullets?

If you’re a “so whatter” – one of those people who are never prepared to be impressed by anything – then you’ll say, “Who cares? It’s just atoms, not real things. So what?”

But atoms are actually the reallest things there are. Are things less real because they are small? Obviously not, any more than thi

ngs are more real because they are big.

No, atoms are real. Atoms are you. Atoms are as real and solid as the book – or the Kindle, or iPad – you are reading.

So how come they can “know” things – like how many slits there are in a screen – and behave differently according to circumstances?

This phenomenon is known in science as “particle/wave duality”, which makes it sound perfectly reasonable until you realize that it is in fact totally bloody impossible and mad.

Anyway, just in case you’re still not impressed, the Mystery of the Magic Atom does, in fact, get even weirder still. But I’ll come back to that.

I guarantee, when I explain the next bit of the experiment, you will be utterly discombobulated.

“Discombobulated”, incidentally, means “confused” or “disconcerted”.

Back in my bedroom, I had become aware of a wobbling sensation, as if the tremors in my hands had spread to my whole body. I felt somehow that I had become one of those double-slit atoms – once solid, but now watery and spread out all over the place. For a moment, I had the sense that I was actually inside the mirror looking back into the room.

If I was inside the mirror, I had no idea how long I stayed there for. The sense of blankness came and went, and I was distantly aware of tiny scraps of stuff happening. I could feel the weight of the book still pressed against my chest. It felt dense and heavy, like a brick. I was vaguely aware of the noise of a far-off police siren. At one point, I saw a spectrum of colours, like light blazing from a prism, but it was only momentary, before everything went dark and silent again. I felt hot, then cold. There was a high-pitched whine in my head, like a giant asthmatic fly buzzing. I didn’t feel afraid or surprised or even think it was weird. I just felt … nothing, really.

Finally, I felt myself falling. It seemed like I was falling a very long way, maybe hundreds of metres, through air that was clear and crisp – sort of mirror-air. But when at last I reached the ground, it wasn’t the ground at all, it was my bedroom carpet. I was spread out on it like someone had dropped me from the ceiling, my arms and legs spreadeagled, one hand still holding on to the book, my face looking straight upwards.

When We Were Rich

When We Were Rich The Seymour Tapes

The Seymour Tapes The Love Secrets of Don Juan

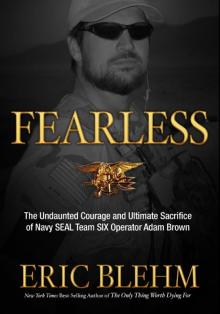

The Love Secrets of Don Juan Fearless

Fearless How To Be Invisible

How To Be Invisible Seymour Tapes

Seymour Tapes The Scent of Dried Roses

The Scent of Dried Roses The Last Summer of the Water Strider

The Last Summer of the Water Strider Rumours of a Hurricane

Rumours of a Hurricane Love Secrets of Don Juan

Love Secrets of Don Juan