When We Were Rich Read online

Page 6

She hands Cordelia the orange carnations. Taking them, Cordelia doesn’t miss a beat.

How lovely. And how unusual!

They’re carnations.

Really? That’s lovely. I’ll put them in water later. For the moment, I’ll just put them . . . here.

Cordelia locates a small litter bin by the side of the telephone table, and places them carefully into it, stalks first.

I hope I’m not being rude. I just need my hands to take the coats.

Flossie is unperturbed.

This is a nice place. Looks about a hundred-and-odd year old.

Built in 1800 originally. Been substantially rebuilt a few times since though.

You’ve kept it very nice.

We haven’t been here for the whole two hundred years, of course.

Flossie hands Cordelia, who is waiting for her to laugh, her coat. Realizing that Flossie doesn’t understand what is expected of her, Cordelia turns her attention to the coat instead.

What a lovely . . . thing

My late husband, Joseph, bought it for me as an anniversary present. Way back in 1975. Real fox fur collar. Careful, it’s a bit lively.

What?

I had it cleaned, but it might still have a few fleas.

Cordelia reflexively holds the coat at arm’s length.

Just joking, dear.

Cordelia’s smile stays firm as she gingerly hangs up the coat on one of six solid brass hooks fixed to the left of the doorway. Michael appears at the living room door. He is wearing red corduroy trousers and a white shirt tucked in, which emphasizes his pot belly.

Flossie. How lovely to see you. You’re looking fantastic. Just fantastic.

I smell lamb, says Veronica, turning in the direction of the kitchen, which lies on the far side of the sitting room.

Well, says Michael, avuncular and glowing. Well.

He notices the carnations in the litter bin and thinks to speak, but a glance from Cordelia silences him.

Shall we go through, then? says Michael.

He plants a kiss on the edge of Flossie’s mouth. She blushes and looks puzzled, then he raises his eyes to the mistletoe suspended above the doorframe and she relaxes. They move into the living room, where there is a hefty log fire burning. Sparks ascend, fading and dying as they climb the chimney breast.

What a lot of books! says Flossie, scanning the laden shelves.

Do you like reading? asks Michael, his red flushed cheeks taking on still more colour from the fire.

Historical romances are about my limit. I like Georgette Heyer.

Why don’t you take a seat? He gestures towards a beautifully distressed sofa.

That’s right, Mum, take a load off, says Frankie.

That’s a lovely settee.

She sits down, grunting as she does so, then automatically slips off her shoes. There is a hole in the toe of her tights. She looks up and sees Cordelia’s expression, then begins to try and put them on again.

It’s fine, Flossie, says Veronica, glancing reproachfully at her mother, who raises an eyebrow in return.

They’re brand new, just a bit tight. Pinching my feet.

Just leave them off.

She is struggling to put them back on, but because of their newness and tightness is finding it difficult.

I’d better check on the meat, says Cordelia, brightly.

Veronica, with an anxious backward glance, follows her mother into the kitchen.

Can I get you a drink, Flossie? Michael says, mildly.

But she is still preoccupied with the shoes and does not respond.

What about you, Frankie? Thirsty?

What have you got, Michael?

I’ve got a twelve-year-old Ardbegh. Very peaty if you like that kind of thing.

I’ll take it straight. Maybe just a splash of water, says Frankie, automatically feeling his jacket buttons, checking that they are done and undone in the right places.

Flossie, flustered, looks up. She has managed one shoe, but not the other.

What about you, Flossie? says Michael, trying again. Do you want something to drink? An aperitif? Perhaps a spritzer. Or an Aperol.

I’d love a glass of plonk. Large. Red if you’ve got it.

Michael nods and smiles.

Or white, I’m not fussy.

Flossie has finally got both shoes back on and inspects, them, satisfied. Michael disappears into the kitchen. There he finds Cordelia and Veronica together, immersed in sinister silence. Cordelia is theatrically checking on the lamb. Veronica is fidgeting morosely in the cutlery drawer.

Drink, anyone? says Michael.

The silence persists.

Am I interrupting something?

Veronica turns sharply.

Mummy has just been telling me – in that underhand way only she knows how to – what a mistake I made when I married Frankie. That’s all.

I wasn’t saying that at all. I was simply saying . . .

Veronica lowers her voice, but hisses plainly.

You were simply saying that Frankie’s mother was ‘a bit rough at the edges’. Which is simply a continuance of a conversation we have had about a hundred times that Frankie is ‘a bit rough at the edges’ too.

You’re being ridiculous. That was months ago. Way before the wedding. I’m amazed you’re even bringing it up. I apologized at the time.

When you realized that you weren’t going to get your way and talk me out of it. And you didn’t apologize exactly. You just said, ‘I’m sorry if I offended you.’

Why don’t you both calm it down a bit? says Michael. I’ll make you a nice gin and it.

He reaches for the bottle of Tanqueray from the drinks cabinet and pours out a good slug in each of three glasses.

You always take her side, hisses Cordelia, closing the oven door on the meat.

How’s that taking her side?

He tops up the gin with a few splashes of tonic and slices of cucumber.

You’re not taking mine, anyway. And you think exactly the same as I do about . . .you know . . .

That’s not true. I think who Veronica chooses is up to her.

Daddy, it’s a little bit true, says Veronica.

No, it isn’t.

Daddy.

Well – a little bit, perhaps. At first. But I think he’s a pretty decent chap, actually. Hard working. Done it all with the sweat of his brow. I admire anyone who can claw his way up. I admit a graduate of Staines Technical College was not the candidate we had in mind, but . . . no need to look like that, yes, yes, I admit it, we were being horrid snobs. I was entirely wrong and I do apologize. Now, can we smooth all this over and have a lovely lunch together?

You’ll see, says Cordelia, attending to the steaming vegetables on the hob.

What now? says Veronica.

Nothing.

What? Spit it out.

Your mother claimed that sooner or later Frankie would ask us for money for something or other.

I never said that! says Cordelia, outraged.

Oh, for God’s sake. Veronica grabs the glass out of Michael’s hand and swigs it down in one.

* * *

They sit down at the dinner table twenty minutes later. Cordelia brings in the crown roast of lamb, greeted by mutters of appreciation from Veronica, Frankie and Michael. The vegetables are already on the table – carrots, parsnips, roast potatoes, kale and butternut squash.

Help yourself, she says grandly, and Flossie does, enthusiastically, covering her plate with everything from the vegetable plates except the kale and the butternut squash. Michael takes the carving knife and begins to cut the crown roast into portions. Inside the meat is pink, almost red. It oozes juices and blood. Notes of rosemary and oregano drift across the table. He begins to distribute the portions amongst each of the sitters, but when he gets to Flossie, she holds her hand up to stop him.

No, thank you, she says.

Frankie looks up from his plate in bewilderment.

&nbs

p; Mum . . .

Flossie shifts in her seat.

I can’t, she says.

Why on earth not?

Her eyes dart from side to side, then upwards into defiance.

I’ve gone vegetarian.

Frankie bursts out laughing.

You’re not a vegetarian.

Florence’s face is set in a stubborn rictus.

It was one of my new year’s resolutions.

Never mind, says Michael.

If you’d let me know, I would have sorted something out for you, says Cordelia crisply.

Well, I couldn’t, could I? says Flossie. I only decided yesterday.

Cordelia stares resentfully at the half a crown roast, £25 a kilo from the organic butcher in the village, that remains on the serving platter.

Flossie finally breaks the ensuing silence.

The plumber came round the other day. I’ve had a problem with my washer.

Flossie’s voice, Frankie notices with alarm, has become louder and slightly slurred. He has rarely seen his mother drunk, she largely abstains, and for good reason as Frankie recalls. Flossie takes another swig of her wine. Now the others at the table begin to attend to their food, starting to eat.

What kind of a problem? says Michael, politely. His soft brown eyes look at her with something like tenderness.

So he comes in. A black chap. Built like a brick . . . outhouse. Six feet tall if he’s an inch. Dreadlocks and everything. About my age though. Maybe a bit younger. He says, what’s the problem? I says, I think it’s the washer. He says, I’ll take a look at that, shall I? I say, do you want a cup of coffee? He says, yes I’d love a cup of coffee. And then I says, black or white? And he says, how you having yours. And I said, I like mine black and strong. He says, you cheeky devil. I said, no, I didn’t mean that, and I didn’t, I really didn’t. I say, I’m not joking, honest, I wasn’t being racially prejudiced. He says, I don’t mind what I have to drink so long as it’s sweet, wet and hot. Then he starts laughing, and I laugh too. You should have seen us. He was nice. I wouldn’t have minded.

Flossie cackles. Throughout this Cordelia has been nodding politely, her eyes somehow both flat and unreflective and glittering simultaneously.

So did he fix it? says Cordelia, voice like dust.

What? says Florence.

The washer?

Florence stares at her.

Who cares?

Mum, says Frankie.

It was just a story. A funny story, says Florence, taking the gravy jug and pouring another quarter pint on to her plate. I thought it was funny, anyway.

Would you like another glass of wine? says Michael, drawing a fierce look from Cordelia.

Lovely, says Flossie. She has already had two large ones.

Do you think you should? says Frankie.

Go on with you. Flossie holds her glass up for Michael to fill. Her white parchment hand shakes slightly, liver spots a faint, emerging constellation. Frankie notices a wine stain on her lips, and smudged lipstick. It’s a nice drop, what is it?

Just something from Waitrose.

She squints at the label, grunts, then takes an urgent swig.

Quite punchy. What proof is it?

Proof?

You know, like, beer has about five per cent. Vodka seventy. Proof.

I’m not quite sure.

Kicks like a donkey.

* * *

After the lunch has been finished, and they have eaten a dessert of passion fruit panna cotta, followed by a plate of expensive and pungent cheese, Frankie and Veronica clean up the kitchen. Flossie made the mistake of putting eggs, then tomatoes, then soft cheese in the fridge, each time having them pointedly fished out again by Cordelia, who has now given up and started knocking back the Poire William. Veronica, against Flossie’s stubbornly vocal protests, has sent Flossie back to the sitting room to ‘relax’. Cordelia announces she is going upstairs to ‘fix herself’ – what this constitutes is not clear. Michael is sitting in the living room doing the Times crossword, while Flossie has now dozed off on the sofa.

Since when has your mum been a vegetarian? says Veronica, as she loads the brushed steel Miele dishwasher, silent as a Rolls-Royce.

She’s not, says Frankie.

Veronica puts another handful of soiled knives into the cutlery holder.

So what was that about?

Frankie hands Veronica Flossie’s untouched Americano.

She doesn’t like the sight of blood. Not on her meat.

Veronica momentarily stops loading the dishwasher.

Why didn’t she say something?

Because she was embarrassed – obviously.

Why?

Because she knew your mother would think she was a pikey for not wanting to eat raw meat. Perhaps she thought being a vegetarian would give her a bit of class.

Cordelia doesn’t think . . .

Don’t waste your breath. She thinks I’m beneath her too. And beneath you as well, since you mention it.

Veronica carefully places a cut crystal glass into the dishwasher. Frankie sees the redness of her fingernail against the transparency and finds it obscurely exciting.

No point in denying it, I suppose, she says, flatly.

And what do you think?

I think she’s awful.

Who? Flossie?

Veronica stares at Frankie full in the face.

Not Flossie, she says. Cordelia.

None of us can help our upbringing, I suppose, says Frankie, touching her gently on the forearm.

He looks around the room.

Nice place this. What’s your dad do in the City again?

He’s retired now.

Did in the City, then.

Something to do with Futures. Whatever they are.

And now?

He’s vague about it. Invests in this and that. A hobby as much as anything else. Bit of speculation here and there. Keeps his mind sharp.

Interesting.

Why is it interesting?

Well. You know I want to set up my own agency one day.

Veronica twists around. Frankie is terrified by the expression on her face. It is one he has never seen before. When she speaks it is through clenched teeth.

Frankie. Listen to me.

What is it? What’s the matter?

Don’t even think about it. Ever.

Think about what?

Getting my dad to invest in some . . . project of yours.

I was just saying . . .

Well, don’t say. Or think.

She is hissing. There are small flecks of spittle at the edges of her mouth.

Vronky! Why are you so upset?

She looks into the living room to make sure that Cordelia and Michael are out of earshot.

My mum thinks you’re on the make. She has said, quite openly to me, that sooner or later you’re going to ask to borrow money.

No, I would never . . .

What do you mean, you would never? You were just talking about it! Don’t say you weren’t.

Well, I didn’t know—

Promise, Frankie, here and now. Promise me you’ll never take money from my parents. I couldn’t bear to see the expression on my mother’s face.

Alright. Christ!

Say it then.

Say what?

‘I promise.’

I promise.

You promise what?

That I’ll never borrow money from your parents.

On the grave of your dead father.

On the grave of my dead father.

This seems to satisfy Veronica, and her face softens.

Okay then. Agreed.

Agreed.

* * *

Colin and Roxy are walking together in the local park, a few hundred yards from Colin’s flat. Roxy is fighting back a headache. Their elbows touch from time to time. Each time, to Colin, is an electric shock. Then, to his amazement, after a few minutes’ walk, she takes his hand.

; I could murder a full English, says Roxy.

Could you keep it down?

Kill or cure.

There’s a café near here. We might be lucky even if it is New Year’s Day.

As they walk, a distant bell chimes. Roxy looks up and notices a spire looming over the hedges that surround the park.

Veronica told me you’re a born-again Christian. She was having a laugh, right?

No, says Colin, simply. Though not so much born again anymore. In the way the phrase is used.

For real? says Roxy, loosening her hand from his but not quite withdrawing it.

He reels her fingers back in.

Not anymore. Not in that sense. I went through a weird time after my mum died. I think I needed something. Someone. Her passing – it scrambled my mind a bit. I sort of depended on her. So I started to go to church. Read the Bible and that. But it’s passed now, pretty much. Don’t get me wrong, I still have a sort of faith. But not in a weird way. I just think there’s a higher power. Lots of people do. You can call it what you want. But there’s more than . . .

He gestures around the park with his hand.

. . . just this grass and rocks and trees and water. More than just . . . stuff.

He regards her steadily, his watery eyes under flickering lids. She looks puzzled.

Do you understand?

Perhaps, she says. When I was seventeen I went through something like that. Joined a church group. Lasted until the vicar tried to feel me up. Sort of lost my faith after that.

I was always a bit late in my development, says Colin. When I was seventeen all I cared about was QPR. That was my religion then, I suppose.

A duck walks past, head in the air, cheerful, in full command of his environment. Colin envies his confidence, feels a lurch in his stomach. Then he reaches in his pocket and pulls out a small transparent plastic bag full of white mulch.

Wonderloaf, he says.

Wonderloaf?

I don’t like fancy bread.

He throws some to the ducks. They ignore it.

Ducks are fussy, says Roxy. Let me have a go.

She takes the bag and scatters some of the bread on the ground. It falls in an almost perfect semicircle. The ducks wheel and start to peck at it.

It’s all about presentation, says Roxy.

They leave the ducks and head for the café on the adjacent road which is small, shabby and deserted but open. Roxy orders a fry-up with everything, Colin a bacon sandwich.

Do you still go to church, then?

When We Were Rich

When We Were Rich The Seymour Tapes

The Seymour Tapes The Love Secrets of Don Juan

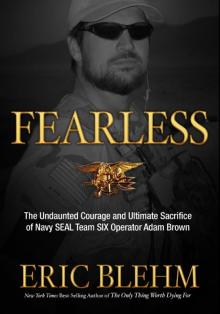

The Love Secrets of Don Juan Fearless

Fearless How To Be Invisible

How To Be Invisible Seymour Tapes

Seymour Tapes The Scent of Dried Roses

The Scent of Dried Roses The Last Summer of the Water Strider

The Last Summer of the Water Strider Rumours of a Hurricane

Rumours of a Hurricane Love Secrets of Don Juan

Love Secrets of Don Juan