The Scent of Dried Roses Read online

Page 19

There are accumulating amounts of pine and white Melamine in the house. They have extended the kitchen, had fitted, coordinated cupboards installed. Jack has put in a lopsided serving hatch. There are concrete rabbits and hedgehogs in the garden, and a honeysuckle arch.

For the first time, the enduring icon of their class has appeared on the mantelpiece. This ornament is owned almost without exception by every householder in subtopia, more ubiquitous even than ornamental egg coddlers or Guernsey cable-knit sweaters. It is a carriage clock. No one, it seems, can ever remember where it came from or who bought it. As if by sorcery, they just begin to appear in living rooms at this time, between the framed family portraits and dry-flower and peacock-feather arrangements. They vary slightly. Some, a sub-genus known as ‘anniversary clocks’, are confined in glass domes. Some have tiny brass feet, some have black-and-white paddles that drive the clock by heat energy. Some have revolving, irrelevant pendulum balls. But otherwise they are identical: about five inches in height, brass or brass effect, roman numerals on a white or gilt clockface, with a small horseshoe handle on top. They are usually driven by a quartz chip and keep perfect time, without noise. Along with log-effect gas fires, they are as specific to subtopia as the Aga and the Barbour are to the Home Counties. The year before my mother dies, she sends an outsize Christmas card to my father, wishing him Happiness for the coming year. The illustration on the front, standing in for nativity angels and decked with bells, holly, ribbons and mistletoe, is a large, mahogany-faced carriage clock.

I develop an aversion for our particular carriage clock out of proportion with its squat ugliness. Its artificiality, its reverence for the past, its mysterious ubiquity, annoy me. I have become, mysteriously to Jack and Jean, something they never were or dreamed of being: a disaffected and restless teenager. I have lost interest in the fortunes of Queen’s Park Rangers and playing club ping-pong, and have sunk into a dull ballet of so-what shrugs.

On the whole, though, the family remains strong, integrated, and the network of friendships they have built up – a core of about five married couples with children who do everything together – easily survives the inevitable squabbles and rivalries. A new pair has joined the circle, Bert and Barbara, he a wealthy, self-made man, gregarious and a bit of a card, she nice, slightly neurotic and shy. They live in Bickley, near Bromley, which, like Ashford or Chalfont St Peter, is the next ladder step from the London inner-outer suburbs.

Jean has a new child, James Allan, two years old in 1970, who roots her life and keeps its story consistent and, in a way, simple. There are glancing blows in this decade which stretch and fray Jean; perhaps they weaken her, and somehow root the sad future. But there is more than enough cause for optimism: most notably, both Jeff and I have made it easily to grammar school, which will guarantee us a low-level white-collar job.

The grammar is modelled on an English public school, although it is coeducational. The head, a diffident woman known only as Miss Smith, wears a mortar board and gown, and the school is divided into houses, St Patrick, St George, St Andrew and St David. We wear green uniforms and peaked caps. The school motto is ‘Loyal au Mort’. In the main corridor outside the assembly hall, there is a wooden plaque with the name of university entrants inscribed. It is a very short list. Most of the pupils, myself included, have never even met anyone who has been to university outside of our teachers and doctors.

The school smells of school dinner cabbage and floorwax. Its teaching approach is traditional and there is a large population of late-middle-aged teachers, furious or bitter or resigned, as they sense the wind of change blowing from the 1960s which will render them redundant or archaic when the school goes comprehensive the year I leave. Most still view knowledge as an unpalatable but necessary medicine which must be routinely administered to wild children, by force if necessary. We learn about kings and queens, about the Empire whose collapse is unacknowledged, for the Empire was benevolent and is indivisible from the idea of England itself. Great store is set on the formation of oxbow lakes, the application of cosines and logarithms, the periodic table. By the time I leave, almost all of it will be forgotten, although I am reckoned a good if slapdash pupil. Despite my final achievement of two mediocre A-levels, I am mired in willing ignorance.

The dry, sexless air that the teachers trail after them, a dim vapour trail, confirms the pupils’ suspicion that education is a mysterious confidence trick at their expense, that it is not the product advertised. On one occasion, someone writes on a blackboard, to the annoyance of the Religious Education teacher, a quote from Ecclesiastes: ‘He who increaseth knowledge, increaseth sorrow.’ And although it is merely a joke at the teacher’s expense, it seems true to us. The impression is further confirmed by the generalized contempt of pupils for the clever or diligent. The untrained but somehow instinctive absence of glottal stops and dropped aitches in my speech provokes suspicion, as does my inflated vocabulary.

You swallow a dictionary, cunt?

This much has not changed since my father’s cousin, Rita, was ostracized for achieving her scholarship and Jack rejected his grammar school place. Thus it does not take long for my natural habit of reading to decay. My voluntary trips to Jubilee Gardens library to read novels – a few modern classics plus a raft of yellow-jacketed Gollancz science fiction – become rarer and rarer, as I realize what the world demands of me – that is, the efficient passing of exams and the wholesale pursuit of experience, sensation, unprovoking leisure and salary. My father’s instinct for conformity, in this matter at least, is passed on.

I have abandoned my childhood persona of being shy, introvert and bookish and have reinvented myself as an extrovert, a loudmouth and a joker. My body has changed now, is no longer a child’s. I have developed an average-size cock which provides me with a hobby which I have come to find more fulfilling than nomination whist or Subbuteo. To this end, I hide, under a Marley tile in the toilet, a single pornographic photograph of an out-of focus peroxide blonde performing oral sex on an anonymous man (he is anonymous because his head has been cut off by the photo crop). It is the absolute limit of my ambition to one day be in receipt of this tantalizing favour. But my hopes are circumscribed; the sexual revolution does not appear to have reached Southall, and girls, so far as I then understand it, remain mainly interested in getting married and procreating at the earliest opportunity. Most have not yet been given the confidence to do otherwise.

My other preoccupations are transatlantic, drawn from the fading shadow of the American counter culture, but this is already in terminal decline. The 1960s have entirely run out of steam and a vacuum ensues. I am vaguely aware that I am picking over the leftovers and bones of a past epoch and that my time, as well as my place, is unformed, ersatz, penumbric.

Like my father, my generation has lives governed by aphorisms, delivered like a virus by one acquaintance after another from schooldays onwards. They are different from Jean and Jack’s, more relative. Now they show the loosening of everything, the lack of interest in consequentiality, the seizing of the present: no one knows anything/everything’s just opinions/why worry? we could all be dead tomorrow/it’s not a rehearsal/money can’t buy happiness, but it can buy a big car to drive round to look for it/just do it/today is the first day of the rest of your life/anything’s possible – they said you couldn’t put a man on the moon/go for it. In a real public school, it would perhaps be Memento mori or Carpe diem.

I am popular at school, although not with my brother Jeff, who is two years above me. The rivalry between us has not abated; if anything, it has worsened. Jeff is the most fashionable boy in the school. He has an earring, which is unprecedented, and long, layer-cut hair. He is persecuted by the teachers and one of them, a Scottish puritan by the name of Jim Hall, nicknamed ‘Jock’, strikes him periodically on the top of the head with the flat of his hand and publicly humiliates him for the acne on his back, which he sarcastically ascribes to the length of his hair.

Apart from the cod

-hippie of my brother, the only other fashion is skinhead, which is more widespread, this school drawing largely from the working-class estates in the area. Haircuts range from a number one (shaven) to a number four (mod-short). The skin girls have feather-cuts or crops with bangs left at the side. The skins wear Sta-Prest, brogues, braces and Ben Shermans, and talk about Paki-bashing, which, to my knowledge, they never actually execute.

Jeff and I wear studded cowboy shirts under our blazers, flared grey flannels, loosened knots in our regulation ties. We are not into peace and love; it is merely fashion. In Southall, no one is idealistic; they are uninterested, or ironic, or mocking. No one goes on demonstrations against nuclear weapons or Vietnam. We are selfish, we have our own lives to kick against. My protests are limited to fits of minor violence. On one occasion I punch the English teacher and only narrowly escape expulsion.

Jeff, unlike me, is meticulous and careful and, in his own way, conservative. He dislikes drugs, dirt and mess, and seems indifferent, so far as I can tell, to sex. He files his records – Jackson Browne, the Byrds, Emmylou Harris, Gram Parsons – in strict alphabetical order, whereas mine are left in a random heap. He hides his comics so I cannot read them, since he has paid for them and considers it unjust that I should benefit. I suspect that he irons them. I search them out and leave them dog-eared, which sends him into a fury and one of the many fights which he invariably wins, being eighteen months older. My impression is that he dislikes me intensely and, in self-defence, I have adopted an identical attitude, although beneath this struck pose, I vaguely recognize that I am desperate for his perennially withheld approval and acknowledgement.

On one occasion we start a fist fight and to my amazement it becomes clear to me that I am for the first time stronger than my brother. I am sporty, he is not, and the muscling on my upper arms and shoulders is beginning to count. The punches I throw are finding their way through and my long pent-up rage gathers within me and achieves critical mass. I feel excitement as I prepare to beat my indifferent, contemptuous brother into submission. I can see in Jeff’s eyes that he knows this also and is worried. Suddenly he sits down, shakes his head and speaks.

For Christ’s sake. Grow up.

The rage in me magnifies. He has finessed me. At this moment, my father walks in, having heard the ruckus, and pulls us apart. I am speechless with frustration. Jeff complains that I am being immature and my father remonstrates with both of us. But the anger inside me that has waited so long for a chance for expression will not be denied. I dart past my father to where my brother sits, quite still now and defenceless on the bed, and I punch him full in the face with every scrap of strength I can muster. I feel a sense of release.

He grabs at his eye, which is starting to bleed. He will carry now his first scar for the rest of his life, still many short of me. My father starts bawling at me, but I break away and run out in the street, enthralled by what I have done, but shocked also. I feel that I am shaking and I want to cry. My anger still reverberates, as if within a soft, hidden echo box. I wonder what its source is, and why it always seems to be present within me. I wonder what it is I should do with it, for it seems to demand discharge, like the sexual energy that finds its way daily into pristine sheets of tissue.

The blow struck at my brother does not cure my anger. Nothing, it occurs to me, ever does. As I walk down Rutland Road and up the hill towards the Top Shops, the rage transmutes, away from my brother and towards my surroundings. The endless blank terraces and dim skies and flat, dull playing fields enrage me further. The sheer absence of the place. I have seen on television, I have read in magazines, that there are other places, places that have focus and shape and meaning. I think of Notting Hill Gate. I think of Mr Salik’s shop. I think of the man in the aquamarine suit. And I think that I have no time, for the ICBMs are waiting to drop, perhaps tomorrow. I am dimly aware, as usual, of a faint but constant panic.

My dreams and fears are mysterious to my parents. They seem rooted and sure, while I am both disconnected from my past and uneasy in the present. Their lives were predetermined, locked into place by circumstance, while I am fired and teased by possibility. This place in my head is unbounded, shameful and absolutely anything can happen. Genocide can happen. The world can be written on silicon. There will be apocalypse, if not now, then soon.

I walk to Jubilee Gardens park, which is empty and puddled with mud and dog shit. I walk to the middle of the football pitch, alone in the park, and shout, as loud as I can, the worst words that I know.

Buggerfuckcunt.

And then, defeated by the silence, I walk back to Rutland Road, with just one thought.

Some day.

Some day what? I do not know. I do not know anything.

The family photographs of this period are badly composed, soft-cornered, often out of focus and disfigured by red-eye and bad fashion. There are also plenty of them, since I now have a Polaroid camera and am prolific with my snaps, which are as shambolic and artificial as my father’s. But the required smiles and raised glasses are not wholly false, even if they fall short of the truth. In many ways, things will never be better for our family.

Jean still inclines towards turquoise eyeshadow and her wig guarantees a sort of enduring youthfulness, meticulously teased and restyled into bobs, curls or loose perms. Mostly she favours a helmet-style neck-length arrangement, slightly piled and fluffed on top, inspired by Purdey in The New Avengers. The hair turns from black to auburn to slightly grey towards the end of the decade. For Jack and Arthur, for Bob and John, the greying is real and the hair at the temples begins to recede. Their clothes are losing the last traces of formality. There is no dominant mode of dressing any more. Instead, a ragbag of windcheaters, Hush Puppies, floral shirts for men, Guernseys and jerseys and cardies. Collars are long and worn outside of crew necks or wide-lapelled jackets. The ties are shiny, too wide, but shirts are more usually open-neck. Beige and muted orange are popular. Jean wears lime flared slacks with sewed-in creases or slightly frou-frou evening gowns, self-tailored or bought from the Grattan’s catalogue, for whom Olive is an agent. She has a pair of Dr Scholl sandals, which she swears by. There are peasant smocks, purple midi-skirts and bell-bottom British Home Store denims.

Both Jilly and David, Olive and Arthur’s children, are married now. Jillly has married Tony, her mod boyfriend. He gradually converted to hippie after smoking marijuana. In the wedding photograph, she wears a floppy hat, and her hair is still unmodified Mary Hopkin. He has extensive sideburns and a dark grey suit and white tie. They will move to Yorkshire and spend seven years on the dole. Tony will become active in the local Labour Party, then leave in despair when it becomes dominated by middle-class wankers. He cannot understand why they choose to talk about blacks, women and gay rights rather than wages and jobs. Years later, in the mid-1980s, he will set up his own business, which will briefly prosper and then go bust. Afterwards, Jilly and Tony will divorce.

At David’s wedding, to Sandy, an infant school teacher, David wears a three-piece flared suit in light beige with lapels that touch the shoulder seams and platform shoes. He has a Zapata moustache and shoulder-length unstyled hair. Technically minded and fond of gadgets, he will spend his working life with what has yet to become British Telecom. He will shortly make investments in eight-track cassette systems and quadrophonic sound amplifiers. James, defenceless, takes the worst of the 1970s fashions, with overlong flared trousers with exterior patchwork pockets, a too-tight plaid jacket and a brown shirt with an orange fat knotted tie. Jean has pulled out her 1960s purple: she wears an ankle-length waistcoat with Mary Quant-style floral buttons, a high-waisted skirt with maroon flowers and a matching cravat. Jack’s suit remains formal, narrow-legged and thin-lapelled. He and Jean are standing in the front garden of the council house at Acacia Avenue on scrubby grass edged with a creosoted picket fence. They toast with Babycham.

There are photographs from package trips to Majorca and Malta, from a camping trip to the Continent.

Jack still insists on posing in his Jantzen swimming trunks, with his increasingly ample stomach very obviously pulled in. Jean is wearing skimpy bikinis, and on one occasion sunbathes topless, to the horror and embarrassment of James. There are blue pools, cloudless skies. In one photo, in Munich, Johnny Amlot bends to fix his Wolseley, which is always breaking down. German cars, it seems, are far more reliable, and increasingly popular, despite the ‘I’m Backing Britain’ campaign once supported patriotically by Jack. But Who won the war, that’s what I’d like to know? is an incantation most frequently uttered by a previous generation. Jack and Jean are not resentful, are generally pro-Europe, and in the 1975 Common Market referendum, they vote Yes. Still, they remain suspicious of foreign food, and make sure to take diarrhoea tablets. In the background, behind Johnny’s stricken car, a wall-advertisement reads: Trink Coca-Cola. Das erfrischt richtig.

Arthur, now a manager for Dolcis shoes in Wembley, owns an expensive camera and is something of a buff, much concerned with the interplay of F-stops and exposure times. At the end of each holiday he will produce a large box of rectangular slides which he will feed into a viewing box or beam on to the wall with a box-projector. Despite his investment, the photos are bad. The time it takes for the correct camera adjustment to be found means that irritation clearly edges the parade of posed grins.

The domestic photographs are more revealing in the background than foreground. There are leaded miniature arboretums, pine clocks, Scandinavian-style furniture from Ercol. There are mirrors overprinted with coloured etchings of an Aubrey Beardsley girl in pink and Marilyn Monroe in green. The ridged, square three-piece suite has given way to studded, golden bronze velour. A print of Van Gogh’s Sunflowers is in the hall. There are ridged pine-cladding, purple curtains, lace nets. There is a coffee percolator, which on special occasions replaces the gruel of instant coffee with an overboiled brown sludge.

When We Were Rich

When We Were Rich The Seymour Tapes

The Seymour Tapes The Love Secrets of Don Juan

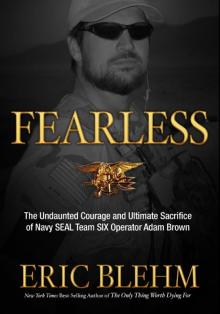

The Love Secrets of Don Juan Fearless

Fearless How To Be Invisible

How To Be Invisible Seymour Tapes

Seymour Tapes The Scent of Dried Roses

The Scent of Dried Roses The Last Summer of the Water Strider

The Last Summer of the Water Strider Rumours of a Hurricane

Rumours of a Hurricane Love Secrets of Don Juan

Love Secrets of Don Juan