The Scent of Dried Roses Read online

Page 20

In the kitchen, Habitat-style half-globe lampshades in ochre. A Morphy-Richards toaster, a Mouli mixer for the sauces that Jean is now learning to prepare for her meats, Espagnole, mornay, curry, followed by Angel Delight, or Bird’s Instant Whip, or Charlotte Russe or pineapple pudding with evaporated milk. Not present in our house, but in snaps from some of Jack and Jean’s friends, are Capodimonte figures of ballerinas and harlequins, miniature, idealized earthenware cottages, valances for the bed bases, pinoleum blinds, Wharfedale Denton loudspeakers. Jack wears a digital wristwatch. The greetings cards on the mantelpiece no longer always rhyme; often they have stanzas by Susan Polis Schultz, a sort of transatlantic Pam Ayres, whose ‘modern’ poetry decorates the inside of cards painted with Jonathan Livingstone seagulls and Californian sunsets.

In one picture, Jean poses with Jack in the garden. It is Jubilee year and he is wearing a plastic Union Jack boater. Although he is laughing at himself, and self-conscious, he is still proud to be English, and proud to say so. Perhaps he is right, for at this time there is still a welfare state and education system and a low crime rate that is, in Jack’s often repeated incantation, the envy of the world. The growing chorus that tells us we are as a people corrupt, racist, colonially brutal and exploitative simply bewilders Jack. For Jack, it is an article of faith that people are basically good, and that the world is sensible and straightforward. When with my father, I ridicule his naivety. But when Jeff makes a visit home from Quebec or Montreal or southern France, I find myself parroting my father, talking insistently about living in the most civilized country in the world, which he decries as a rotting, rinky-dink, penny-ante dump. As is habitual for me, I am not sure which I believe; my opinions change according to circumstance. I ache to own a belief, a conviction, but nothing seems incontrovertible, everything is plausible.

Around the same time, Jean and Jack are on the velour sofa, newly pine-clad walls reflecting a photo flash behind them. Jack is asleep, Jean has her head on his shoulder and is smiling with a look of deep contentment. She loves her husband. It is always Jean who moves to him and says, Go on, give us a cuddle. He is pleased, always responds, but never makes the first move himself, not thinking it manly. After Jean is dead, he will regret this and give me one of the few pieces of advice he ever offers:

Always show affection to your wife. Tell her you love her.

There are few photographs of Jeff in this time, because he has fled England at the age of eighteen, never to return except for brief visits with foreign girlfriends. What pictures there are show him boiler-suited or tanned or in ragged T-shirts. He becomes itinerant, working at one time in a French youth hostel, at another as a pony and trap driver in Quebec, kicking the horses with an adopted Gallic indifference. To my parents’ bewilderment, he has become obsessed with something called ‘authenticity’, the quest for which explains the plainness of his clothes, his working man’s beard and his labourers’ boots. A typical shot shows Jeff in France in front of a Christmas tree with his French-Canadian girlfriend. He is wearing a peasant neckerchief and denim, she is wearing a boiler suit and working shirt. The inscription on the back reads: ‘This is us in front of our real Christmas tree, Dec 76’. It is a reference to the fact that we have lately taken to buying a plastic one, since the real thing produces too much mess. Neither Jack nor Jean tries to bind Jeff to home by the subtle application of guilt or appeals to self-sacrifice; as Jack repeatedly asserts, You have to let go. Jean says that she agrees. In this way, she seems to prove herself strong as well as dutiful.

The remaining photographs suggest that Jack and Jean’s life is still good. They live in security and more or less without fear, for the present or the future. They pursue leisure, increasingly available. The pictures show ‘relaxation’ and ‘activities’ and ‘recreation’. Here they are at the Acropolis Restaurant in Weybridge, on the anniversary of friends. They are drinking retsina. Plates will be smashed later in the evening and Greek dancing attempted. Unlike me, they lack the self-importance to mind making fools of themselves. Jean and Helen pose with roses clenched in their teeth. Here they are at the Old Orchard in Harefield, where they go for dinner-dances, which have by this time more or less replaced ballroom dancing for their generation. Jack still moves beautifully and is a sought-after partner.

Here is Jean at evening classes, doing yoga and flower-arranging. She goes with Olive and takes the lead, since Jean makes friends easily, unlike Olive, who is slightly diffident and shy. Here’s Jack playing badminton, his Carlton, cat-gut-strung racquet poised over his head in an overhead smash. He is a good player, tactical acuity more than making up for his unschooled, improvised style. Like my mother, like me, he will be determined to win. There are shots of more holiday camps, restaurants with flock wallpaper, sun on the fields of France and Germany, of Luxemburg and Belgium.

Occasionally they will glimpse themselves on television, in Terry and June or – Jean’s favourite – Butterflies, with Wendy Craig as a dreaming housewife with difficult but finally lovable sons. Or they will go to the Richmond Theatre or the Alfred Beck Centre in Hayes to see Jesus Christ Superstar or a revival of one of their old favourites, Carousel or Seven Brides for Seven Brothers. They will not go and see Mike Leigh’s Abigail’s Party, that cruel, inaccurate satire of subtopian life – it is ‘theatre’ and therefore ‘arty-crafty’ and so not really entertainment as such.

Jack and Jean, who have never expected much from life, are in fact satisfied, far removed from Mike Leigh’s grotesques. Yet shadows are inching towards Jean, as they did in the photograph of her at sixteen years old, on a dustbin in the garden at Rosecroft Road, across a dry garden path.

For me, this is a time of success, at least measured against the expectations of my background. Jean and Jack are proud of me, but they do not say so, believing that it will encourage conceit. In fact, the insecurity this restraint engenders in me produces exactly the effect they hope to avoid. I become increasingly cocksure, almost as an act of defiance; my deeper feeling is quite different.

Jeff does not seem to have an opinion on the matter of my exam success. His unexpected failure in his A-levels has not done much to bring us closer and his self-imposed exile does not give us the time to properly reconcile our childhood rivalries. When we meet occasionally over the following years, the atmosphere of competition and resentment is palpable.

I have developed a defensive arrogance that makes even people who like me dislike me simultaneously. Yet the effect on the whole is what I hope for: people find me interesting and seek me out. I am not ignored, even if I am not always liked. Furthermore, women are attracted to this arrogance, mistaking it for self-confidence.

This expression – apparently self-assured, bolshie, as my mother will have it – is the only constant in the photographs of me at this time. Otherwise I am in an endless state of transformation, as if hunting some condition of rest. I am trying to make myself up. I am searching for ballast, the ballast that was my parents’ birthright.

Here I am in schooldays, my hair long and girlish, in a mauve satin jacket and a purple yoked cowboy shirt, in platform boots and loon pants with triangles of cloth sewn in to accentuate the flare. I leave school in 1974. I have found a place in further education.

Here I am at technical college in Harlow, where my father trained as a matelot, before it was a new town. I am taught tabloid journalism (thirty-five word intros, give it spin, build the story like a pyramid). Most of the writers on the course will go on to provincial locals, or, if they are lucky, the News of the World or the Daily Star. One of our chief lecturers is a reporter from the Sun. The course chief is a sports reporter from the Daily Express.

My hair has been shortened, layered, and I have smartened up into a dog’s-tooth jacket, thick tie, polka-dot scarf. I am wearing yellow aviator spectacles and have a Zapata moustache which pulls my mouth downwards into a dimwitted droop. I look like a fool, but then, it is the 1970s. Everybody does.

Here is Debbie, my first girlfr

iend, whom I meet at college and to whom I lose my virginity. I am enthusiastic about sex, about sensation in general. I want to live in a Bacardi commercial, or Benson and Hedges poster. I want self-transcendence, perpetual delight. My thoughts are not consecutive enough to frame limits; there seems to be a strobe running somewhere. Still, I am happier than I will ever be again in my life, here in Essex, the spiritual home of my class. I have succeeded in deflecting certain unsettling questions into relentless activity. I conspire, along with the rest of the world, to limit introspection. Lights flash. Loud music sounds.

Debbie is an attractive, warm, too-pliable girl from an ordinary family. She is from the inner city, in this case, a tower block in North Kensington. We work meticulously through the pages of Dr Alex Comfort’s Joy of Sex. I have even sprouted the beard of the Californian-looking protagonist in the tastefully pencil-sketched pages. I wear plaid bum-freezer jackets with fake-fur collars, Afghan coats that smell like damp yak, purple platform boots, Donald Duck shoes, shirts with collars like ox tongues. I have an army greatcoat, bell-bottom Wranglers bleached and frayed at the bottoms, fitted leisure shirts from Michael’s Men’s Boutique in Ealing Broadway. I have grandad vests, lapels like Dover soles. Everything is inelegant, toylike, parodic without being ironic.

The next set of photographs shows me employed on a local paper in Uxbridge, five miles west of Southall, where I hone my craft of the brief sentence and the artful cliché. I learn a specialized kind of lie which I am trained to understand, in my bones, as being true.

Here the houses are more widely spaced, smarter, and the residents have two cars and garden sprinkler systems. Jean has talked of moving out this way lately, but they are insufficiently well off. The photographs, often newspaper 10 X 8 black-and-whites, show someone unmistakably prosaic, suburban, mildly laddish. My T-shirt and jeans, my haircut and shoes, still tend towards American casual. I drink until I am sick at parties. I have a faint sense that I am doing what is somehow required of me, but it is only faint. I am garrulous, determined, proudly ignorant, on the make. I have given up reading books.

It is 1976, the year of punk, when England begins to reimagine itself as it really is, or as it is becoming. Rage stands in for nostalgia, junk is virtue. McDonald’s boxes begin to litter the streets and Covent Garden, where my father and grandfather have plied their trade, has been turned into a covered shopping mall. I am employed on a national pop music magazine, at the heart of it all. I have left home and am living in a freezing basement flat near the Harrow Road, decorated with ironic flying ducks and 1930s knick-knacks. The photographs, Polaroids with faded colours or press half-tones, show that the beard has gone, as molecules of the trash aesthetic rub off. My hair shortens further and I wear black drainpipes, rocker jackets, tour T-shirts, thin ties and lapels, narrow-toed boots. I shop at PX in Covent Garden and buy boiler suits and camouflage jackets from Lawrence Corner.

The photos show me with the celebrities I have begun to interview, my heroes of the time – David Bowie, Bryan Ferry, Kraftwerk. Here is me with Freddie Mercury in his Kensington garden, and here with Poly Styrene of X-Ray Spex, Paul Weller, the Clash. I am frightened of the people I interview, suffer a kind of vertigo each time. I overcompensate for my secret shyness by thickening my patina of arrogance. Yet I am also amazed that they are so unremarkable, so prosaic.

The world has changed for me utterly now. I am flown all over the world. Before this job, I have only eaten in a proper restaurant once, on my eighteenth birthday. Now I eat in restaurants with Michelin stars. I drink bottles of wine worth more than my father’s weekly wage which I cannot appreciate, order food from menus which I cannot understand. Here is me in LA in a white stretch limo. Here I am in Barbados, in my own hotel suite. Here I am at the George V in Paris, the Essex House in New York. It seems that my childhood instinct is right: the world is without limits, if you are smart and determined and lucky. And daily perhaps, I ask that question, that burden of my generation, am I happy? And daily, the answer comes, it is not enough. It is never enough.

Here is Marion, my second girlfriend, whom I take up with after three years with Debbie. She is dark at first, then turns bleached blonde, after which she becomes promiscuous, in retaliation for my own unfaithfulness. I find myself living with her after she is made homeless and she moves into my flat. The spreading vacuum within me reaches out to her to look for something solid and finds only more empty space. I push and bully her to elicit some definite boundary, but the more I push, the more she collapses. Like me, she has no opinions, no convictions, no real beliefs, only an instinct to jump on to the next raft of experience. Her reliance, her strategy, is habit, instinct, niceness. We are weak, without self-knowledge, we torment each other, both unfaithful, both too dependent. Overweight, she suffers from bulimia and causes herself to vomit in the toilet. In the end I leave her, as I have left Debbie, with some amazement at my suddenly found strength after years of vacillation. It is 1979 and I am twenty-three years old.

By this time the photographs have changed once more. On cue for the coming decade, I have set up my own business, a news agency, with a partner, again from my background. I am smart, with expensive clothes and sharp, gelled hair. Oh, we are on the rise, my class, the C2s, the Essex Men. We have money, we have opportunity, we have hope. My partner, a clever and garrulous man who grew up in a council block in Islington, has no doubt where the future lies.

Something special is going to happen with Maggie. Yes, you can laugh, but you’ll see. This country’s going to be great again.

And it is true, it does feel like a new era is starting. Money is coming in. The grammar-school generation are biting the hand that fed them and voting in their millions for an end to soft consensus, slow drift. They want something firm, something they can bite on. Although I am unconvinced and put my cross in the same place my father always has, I feel the change. People believe in fairy-tales now, in anything at all, and are voting for them. People believe that the impossible is possible, that everyone can be rich if they try.

And sure enough, I am soon to be rich and in constant motion forward. How will it feel, I dream at this time? What will it be like to have that special thing? To have money. Will it make me real, bring me into focus? I dream, I plot, I prosper.

Chapter Twelve

‘Struggling against impossible odds, surrounded by children, poor housing facilities and little money? These neuroses usually respond best to therapy with Triptafen’– 1970s medical advertisement

Facts, there are so many facts. I have left such a lot out. There must be many more unremembered and still more unknown. If I had chosen differently, it would be a different story, but this is the story I have told myself and I must hold to it. It is a trick I am trying to learn.

I need a story and that is the nub, that is what it boils down to, as my father always says. I need one like breath, one that sticks, because they are always coming loose, floating away. Others rise up from underneath and take their place, then in turn fall and fade. They focus, then blur, focus, then blur. It is very – disquieting. It is dangerous, not knowing the shape of your own life. I have made that mistake once. I have had that flaw, if flaw it is.

So I must carve and sculpt, I must select and discard, I must hold fast to the narrative. Perhaps I am indulging myself, lying, writing the autobiography of a nobody, for nobody but myself. It often feels that way. There are few clues to tell me that I will one day go mad, unless ambition itself is a sort of madness. There are few clues to tell me that my mother will go mad, unless connectedness – family itself – is a kind of madness.

Two things happen in the 1970s which loom large in this particular version of my story. They seem consistent, are always presenting themselves to me one way or another as I daily pick over the past, that unfinishable, indigestible feast. Perhaps this means they are significant. I will come to them, these scraps of story, but let me first put these questions, questions to which I do not have an answer. Does the human mind behav

e like metal? If put under enough strain, does it fatigue and weaken, so that one day the slightest wind will snap it? Or is it like a reed, bending, then flexing back into place, without damage? Is it rigid or is it elastic? Is it soft or is it hard? Does it have a true past which takes action on the present or only an endless, enveloping present in which we simply imagine a past?

It is a beautiful sunny afternoon, a Sunday. Jean and Jack are playing tennis with their friends at Duke’s Meadows in Chiswick, as they have done on Sundays for years. I am fifteen years old, with hair down to my shoulders, splitting at the ends, greasy and darkened in the centre parting line. I am bored, for too many reasons to list.

I begin to walk, down towards the Yew Tree roundabout in Hayes. I have taken to idling around the common ground on the high-rise estate there facing the Yew Tree pub, where I have a friend called Donald, who goes to a local secondary modern. It is an ugly estate, system-built, white. Donald and I often stand and share our ennui, as if it were a cheap cigarette. We indulge in minor vandalism or drink VP sherry or Olde England Cherry Wine. There are girls there sometimes, plain ones in postal-catalogue polyester and nylon. We take them into the underground garages and try to find the courage to make rudimentary sexual advances, but fail. I am shy, ashamed of my scars and my oddly refined voice. Instead we kick the ground and skirt the subject. Hours will pass before I go home, nothing achieved.

On this occasion, however, I am not going to see Donald but another friend, Graham, who is older than me, has short hair and wears a parka. He also lives on a council estate, across from the blank high-rises, in a six-house terrace. In later years, he will become an ultra-right-wing Conservative councillor.

I walk down the Greenford Road, over the bridge, past the Taylor Woodrow factory. I do not know what it makes, but some of my father’s bridge partners work there. Sweat marks my scoop-neck long-sleeve T-shirt with the flared sleeves. I have an attempted moustache, a faint line of fur. An uncommon feeling of anticipation beats in my chest. Graham has a surprise for me and I have an inkling of what it is. I am very slightly frightened. The sun is relentless.

When We Were Rich

When We Were Rich The Seymour Tapes

The Seymour Tapes The Love Secrets of Don Juan

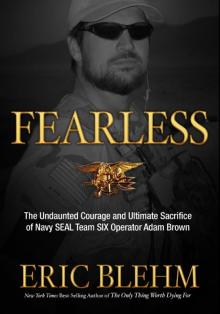

The Love Secrets of Don Juan Fearless

Fearless How To Be Invisible

How To Be Invisible Seymour Tapes

Seymour Tapes The Scent of Dried Roses

The Scent of Dried Roses The Last Summer of the Water Strider

The Last Summer of the Water Strider Rumours of a Hurricane

Rumours of a Hurricane Love Secrets of Don Juan

Love Secrets of Don Juan